|

This month, I plan to continue to highlight the evidence based practice of establishing the ‘function of behavior’. As I highlighted last month, in the introductory article (part one), this is such an important strategy to understand and highlight as the function of behavior, or more simply the ‘why the person is doing what they are doing’, ultimately helps establish a more successful response or strategy. This is a foundational understanding when trying to support anyone, but especially someone with autism. This can be more difficult for non-verbal people but there are many other ways to communicate the why of a certain action as well. Please see the October edition if you wish to see the first part of this article for the background information. As we search for a true solution for supporting someone when looking at the function of behavior, we need to be careful about how we discuss the situation. For example, if we are describing someone as “lazy”, what we observe may be that the learner does not complete the task they doing. Why might this be the case (true function of behavior)? The work or task may have been too difficult, too easy/understimulating or the performance may not have been consistently reinforced. That is to say, the learner may have needed more verbal praise or visual reminders to keep them motivated and interested.

Another example could be that we are describing someone as “violent” and what we observe may be that the learner is hitting others. Why might this be the case/the potential true problem may be? The learner may be trying to ‘get suspended’ or taken out of particular situation they actually find undesirable. The learner may get peer support or admiration for being tough and feel they are gaining power or respect. A learner may be getting different forms of reinforcement as a result of this behavior. There could be a sensory issue. I remember my own child, when he was a toddler, would hit me violently when he would get hurt at all. It seemed so unexpected and this was pre-diagnosis so I was genuinely confused at his violent outburst. Pain sensitivity played a part I suspect now. Another situation, one may describe a learner as “oppositional” when we observe the learner protesting when directions are given. What may actually be the case could be that the task is simply too difficult, the task was not chunked small enough, too many verbal instructions were given, the directions were just not understood, or the learner has experienced that by protesting before the task begins they are sometimes allowed to avoid the task altogether. I remember trying this myself as a child when it was time to clean my room: when my mother was tired, I realized she would give into my ‘tantrums’ more easily and I could avoid cleaning my room at all. Remember, these strategies are good for all, critical for some…. Lastly, I will highlight that we need to recognize and respect the energy levels of the learners (any age). Behavior can fluctuate from day to day or even hour to hour. What was possible one day may not be possible the next or vice versa. Remember to keep these questions in mind: What am I asking of him/her? What has he/she already done? How taxing has the day been so far? How taxing is the event or task coming up? Does he/she need a break? What are their current behaviors trying to communicate to me? For example, what one can accomplish after a great nights’ sleep and hearty breakfast may differ from what one is able to do after a long day of work or when feeling cold, hot, hungry, tired, etc. When you are trying to determine the true function of a learners’ behavior, it is important to follow a few key steps:

0 Comments

As you may have noticed, I had been writing a regular column highlighting one of the 28 evidence-based practices (EBPs), otherwise known as ‘things are have a lot of proof behind them that they really work’ in helping people with autism (Steinbrenner, 2020). This is a recently updated list from Wong’s earlier work (2016) outlining 27 EBPs. As an educator involved in the field of inclusive education and as a parent working to support my own kiddo, I am all about finding what really works and excited when new developments like this occur. Regularly, I plan to highlight one of these 28 EBPs for you.

When we talk about deciphering the function or ‘why’ of a behavior, it is important to define what the word ‘behaviour’ means. Shane Lynch tells us that, “Behaviour is anything and everything: every observable action by a person is behaviour.” However, “observations do not provide an explanation of the behaviour”. Lynch warns the observer to remain objective when observing and also the importance of ruling out any medical biologically-based behaviours.

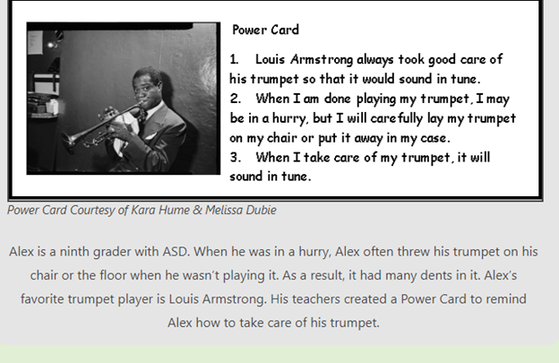

Lynch goes on to explain that behavior occurs for one of two reasons. The students is either trying to get something or trying to avoid something. If we can keep this in mind and try to target what they person is getting or avoiding then we have a better chance at making changes to adverse behaviors. For example, the person may be trying to attention/reactions, items (tangible), activities, automatic reinforcement or sensory stimulation. In terms of avoiding, the person may be trying to avoid work, sensory overload, transitions, social situations or unwanted sensory stimulation. I read an article recently about some students at a school who were having issues that seemed out of character for them every springtime. Winter would be no problem but as the weather warmed up and the students lost their heavy winter jackets, hats, mittens and heavy boots, there seemed to be new behaviour problems. Once the parents and school personnel realized that the students had been benefitting from the sensory input of the tighter heavier winter clothes and enjoying the positive pressure that had been providing, it was easier to come up with more appropriate solutions. If one did not realize it was sensory related, it would have been much harder to help support. This would not have been my first thought so this information is very helpful when trying to see situations through a new and helpful lens. If we do not determine the reason/function behind the behavior, we may end up trying different strategies or interventions that are not going to make any difference at all. For example, if a child is throwing a tantrum at the grocery store each time, it could be because they are hungry for a treat, want your undivided attention, are tired if its always right before naptime, find the smell of the meats undesirable, just don’t like doing the work of unloading the groceries afterwards, the having to stop their play or other desired activity to go and get the groceries. Each reason could be legitimate but figuring out the ‘why’ will aid in overcoming the difficult response. Trying different strategies to address the wrong ‘reason’ the person is having difficulties can make the responses more intense or cause more harm than good. This is like taking a shot in the near dark and hoping for the best. Research supports this as we read, “Furthermore, random selection of an intervention can result in a lengthy process of trial and error, which may negatively impact a learner's educational process and social interactions, or may serve to strengthen problem behaviors.” (AIM module.) The overriding goal of all educational/behavioral interventions is to increase an individual's skills in order to help him/her function independently in a variety of environments. Functional behavioral assessment (FBA) is much more than a procedure; it is a process and a way of thinking. FBA can assist teachers, parents and caregivers by determining when, where and why which should lead to a smoother and more independent situation for the learner. For example, if someone is trying to avoid some work that they are required (and able) to do, ex: putting away their laundry, they may try things like changing the subject, procrastinating, starting other preferred activities, etc. If you provide a highly desired tangible item (something the person really enjoys but has no regular access to) if they put away their laundry, you may have a better chance of that happening (achieving the desired outcome/behavior). The learner may really want positive social interaction, compliments, high fives, smiles, etc. to help them get the work/task done and by providing that during and after you may also get a better outcome. Try to consider what the learner will want to get or avoid to guide your next response. Look for part two of FBA strategy in next months’ edition where I will further flush out this information. Remember: figuring out the WHY will get you closer to determining a more successful NOW WHAT solution to the issue.  This month, I plan to continue to highlight the EBP of ‘social narratives’ (third and final installment for SNs). SNs are typcially associated with ‘social stories’ but it is broader as we will also discuss ‘power cards’ too. Part one outlined a huge list of goals that this strategy can help to address and these can help decide if this is an appropriate strategy to try. For this third part, we will look at more specific examples of social stories and power cards and more bits of related information. The research shows this is effective from the ages of 5-22 although if you wanted to try it with older or younger learners then I would do that. Much of the information in this article is from the related AFIRM online module (link below). Social Stories help learners with ASD understand the situation and other people’s perspective. Power Cards use a learner’s special interest to describe rules and behavioral expectations of a social situation. You can use this general rule of thumb when deciding which one you should choose to address a certain goal. In the last article, we discussed steps to consider when creating a SN. Here is a bit more information on Power Card creation in particular (still considering the general suggestions outlined previously). Power Cards typically involve a scenario that the learner may find challenging in some way (behaviorally, academically, socially, etc.). Then, a list of expectations or rules are clearly laid out to follow. These can be created on index cards for example and can be kept (laminated for durability if needed) for regular reference. They are portable so are easy to take to different locations if needed or applicable too. The learners’ special interests can be incorporated into the power card too. You can write them specifically for the situation and learner to help personalize it and address the specific goal (but you can purchase premade ones as well). See examples provided. Whether you choose a social story or power card, find a distraction free space to introduce and use it. The learner will be able to focus on it and the chance of understanding will go up. Explain to the learner what the social narrative is about and the important aspects to keep in mind while reading. After the learner has read the social narrative (or been read to depending on the age/reading ability), ask the learner three to five comprehension questions about the narrative. The learner’s answers will help you determine if the learner understands the concepts in the narrative. Consider using role plays to provide the learner with an opportunity to practice the target skill or behavior. SNs are also proven to work better if read/shared/reviewed directly before the target behavior/situation is about to happen. For example, if the learner is about to go for a job interview, reviewing the SN right before the interview is the best bet for success. Social stories or power cards can be an effective tool when discussing more personal or sensitive topics (hygiene related, relationship related, etc.) as well. It can help to lay information out clearly and plainly in a way that can help the learner to understand. Having text and/or pictures can be helpful as well in terms of providing extra context and information depending on the learner’s ability to take in new information. It can also help to have a focal point to look at when discussing sensitive topics. If you want more information how to begin to use SNs, create them (or purchase), whether they be social stories or power cards, ask your child’s school/teacher, a speech pathologist, any autism specialist or do your own research as there is a lot of information about it. I have witnessed the power of this strategy work firsthand and firmly believe in the power of SNs. This tool can (and sometimes should be) used in conjunction with other strategies (such as visuals, prompting or using reinforcement for attention and/or success) if needed as well. Look for part one of the next evidence based practice for another ‘power tool’ for your proverbial ‘tool kit’ of what is proven to work. If you are interested in checking out the free online AFIRM modules, here is the link (will take you to the social narrative module in particular as I am highlighting this here). https://afirm.fpg.unc.edu/node/589  As you may have noticed, I have been writing a regular column highlighting one of the 28 evidence-based practices (EBPs), otherwise known as ‘things are have a lot of proof behind them that they really work’ in helping people with autism (Steinbrenner, 2020). This is a recently updated list from Wong’s earlier work (2016) outlining 27 EBPs. As an educator involved in the field of inclusive education and as a parent working to support my own kiddo, I am all about finding what really works and excited when new developments like this occur. Each month, I plan to highlight one of these (now) 28 EBPs for you. This month, I plan to highlight the EBP of ‘social narratives’. SNs are usually associated with ‘social stories’ but it is broader as we will also discuss ‘power cards’ (which may be a new term to you). This will be part one of a three part series highlighting this one strategy. Much of the information in this article is from the related AFIRM online module (link below). Why choose to try a social narrative? They are a great tool to describe social situations by providing relevant cues, can help to explain the thoughts and feelings of others, and provide descriptions of appropriate behavior expectations. SNs can be effective with very young to young adult: pre-school (3-5 years) through to high school age (15-22). SNs are being used in many environments by teachers, paraeducators (EAs), interventionists, and parents and family members. Talk about a versatile tool! Social narratives can address a TON of goals. Here are a few:

For instance, I had read a story about how to navigate time at the mall, which had included a food court page in the story. Within the story, one character had their ice cream fall out of the cone onto the ground and although the story explained that he was very upset, he took a deep breath and calmly asked if he could get it replaced and that worked as a viable solution. I hadn’t thought much of it at the time, but fast forward six months later and I am at the mall food court with my own kiddo. He had ordered fries and accidentally knocked them onto the ground before eating any. It was like time froze for both of us for a split second (maybe just for me…) and I could see the panic in his face. I braced myself for a possible meltdown but, to my great surprise, he took a breath and slowly forced out the words, “Is this just like the time Tommy dropped his ice cream and just asked for more and it all worked out? Should I just ask to see if the fries can be replaced and see if that works out?” Honestly, it took me a minute to remember the social story we had read those months ago but once I did and got over the shock of his measured reaction, I nodded emphatically and got him new fries as fast as possible. It was such a relief and positive experience with the help of that social story we had read together! Things are always more convincing once you see them work so effectively with your own eyes – not simply trusting that it is an evidence based practice. As I mentioned earlier, there are two types of social narratives: social stories and power cards. Social Stories - describes a social situation and the viewpoint of other people, and provides strategies for the learner. These can be as simple as one graphic with information and pictures on it or as long as a full story with multiple pages that share a narrative with some direct teaching as well. Power Cards-consist of 2 parts: a brief story scenario and a Power Card which is a small card with rules outlining behavioral expectations in the social situation. You can incorporate pictures of learner’s special interest into both the scenario and Power Card. Look for part two of this series to find out more about how to use social narratives in your own home or work to benefit a learner in a really creative, concrete and accessible way. This is another ‘power tool’ for your proverbial ‘tool kit’ of what is proven to work. If you are interested in checking out the free online AFIRM modules, here is the link (will take you to the social narrative module in particular as I am highlighting this here). https://afirm.fpg.unc.edu/node/589  Last month, I related the practice of effective prompting to ‘leading a dance’. When you are dancing with a strong lead, you (typically) really enjoy the dance, led seemingly subtly, into a successful dancing experience. I want to re-iterate this point. The use of prompting can easily fall into the category of over or under prompting and can seem to lead to frustration or overreliance. Prompting requires a purposeful and cognizant approach to be both respectful and successful. Part of this, is knowing how and when to fade a prompt, which I will cover in this article as well. Fading the prompt is one key element in the usage of this evidence-based practice. So how can we do this? What more can we learn beyond last months’ information on the five types of prompts and the uses for it? (In case you missed it, we highlighted these types of prompts: visual, verbal, gestural, modelling and gestural.) When a person is practicing a mastered skill, one should be using “least to most” levels of prompting as needed. Do not over prompt (even though it is very tempting and may feel natural/supportive). For example, if someone is used to making their own breakfast, they may only need a gesture to remember to set the timer. If a small verbal reminder will help them to turn off a burner, that is more acceptable than repeatedly modelling or giving full physical supports like hand over hand when they are capable of completing the task. If no prompts are needed, do not provide one for the sake of providing it or because that is “just what we do”. For example, I hadn’t noticed that I was continually running my finger under the words as my son read them until he let me know that he does not need that at all and can now read without that prompt/support. He had outgrown it and I did not notice. Alternatively, when a person is learning a brand new skill, then the “most to least” level of prompting is recommended. Give the person as many supports as needed initially when learning something new so that they can experience full success and have a decrease in possible anxiety when facing something new. Providing enough support at the beginning of learning a new skill or task will increase feeling of success and they may be more likely to try the new skill or behavior the next time. For example, if starting a new job, the person may need specific training on how to set up their work area. A co-worker could walk them through it as opposed to giving the information verbally once. One type of prompt that I used a lot as both a parent and classroom teacher was musical prompting. This is close to verbal prompting but more fun, less intrusive, and tailored to their favorite genre of music/favorite songs, etc. For example, having a certain song playing to indicate that it is time to get dressed for school or ready for work is much nicer (for everyone) than verbal prompting (sometimes can be ‘nagging’…). Different songs can mean different things or ways to transition from one activity to another. As much as prompt usage can be key, fading the prompt properly and in a timely manner can also be a key factor in increasing independence and ability. We need to look for opportunities to fade a prompt to less intrusive to none at all if possible. This can be difficult as we may feel the prompt is the key to success, avoids a meltdown, or we don’t want to give it up for another reason. For example, I had made this effective visual for my kiddo that helped him to answer the door and greet our guests successfully. I was actually really proud of it and it worked! I was hesitant to take it down though even when he could successfully do the task on his own. We need to ensure that we are evaluating if we are not fading the prompts quickly enough or even at all! We use this evidence-based practice naturally and is second nature to most of us most of the time. I am simply highlighting a need to examine the levels of prompting we are providing and see if there are ways to use them, fade them, and ultimately build more independence and self-advocacy skills. Maybe this article will ‘prompt’ you to think about it!  When I think about prompting, I usually relate it back to the analogy of ‘leading the dance’. When you are dancing with a strong lead, you (typically) really enjoy the dance, led seemingly subtly, into a successful dancing experience. As a terrible dancer myself, I can attest to this! In the same way, if you are giving the appropriate level of prompt, this guidance is in a ‘just right’ manner. It is respectful above all: a clear intent to avoid over prompting as much as one avoids under prompting. The intent is to be ‘just enough’ help to avoid errors/mistakes but allowing the person to still build skills and confidence in the act. This is definitely harder than it may appear at first sight and there are a few key points in learning how to support a person with autism with proper prompting strategies. “Prompting includes any help given to a learner that assists the learner in using a specific skill or behavior” (AFIRM). This EBP can be used to help a person to meet academic, social/emotional, professional/work related or personal goals. We typically think of five different types of prompts. Five Types of Prompts

This strategy really has so much to it that I will highlight it again next month! I will go a bit more in depth and discuss how and when to successfully fade a prompt when possible as greater independence and true confidence and achievement is a major goal.  This month, I will continue to highlight the EBP of ‘reinforcement’ (hence the part 3 in the title). Since there is so much to say, know and do with this powerful strategy, I decided to write multiple articles on the usage of reinforcement. Much of the information in this article is from the related AFIRM online module (link below). In this third part, we will explore a few basic misconceptions around the use of reinforcers as well as some potential problems and solutions to these should they occur. For some reason, there are people that are automatically against even exploring the use of reinforcers. This is puzzling to me as I know I appreciate a compliment, kind word, unexpected gift given or, the most obvious example of a planned reinforcer, a paycheck from work. I love my job but would not be going without getting that regular ‘payoff’/reinforcer… Isn’t this just the same thing as bribing though? Used incorrectly, it can be, yes. Here are some differences though: Reward: earned as an incentive for a job well done. Bribe: given in response to a challenging behavior. Reward: create a lasting positive change on behavior Bribe: changes behavior in the moment but not over time Reward: planned ahead of time and delivered with praise Bribe: reactive and delivered in frustration Reward: adult is in control and decides if the reward is earned Bribe: child is in control/negotiation is made in exchange for compliance *above two in terms of working with children (Behavioural Interventions and Solutions, LLC, 2019) The secret to the successful usage of a reinforcer is really more of how it is used instead of the what. This is more about the intricacies of using the strategy (applies to all strategies). I use the analogy of ‘leading the dance”: when done properly, the person led feels supported and is definitely enjoying the experience. It can be very intricate in how you support/fade/prompt as it can is intentional (which can be exhausting at first) but definitely worth it! It has made a huge (very positive) difference in my work at home and school. There are some common problems when trying to set up or use a reinforcer. Here are a few with possible solutions: P1) Learner was making progress with target skill or behavior but recently became uninterested with the reinforcer. S1) Satiation has occurred (the reward was used too often and now the learner is ‘bored of it’). Conduct a ‘reinforcer survey’ (mentioned in past article) to identify new reinforcers. You may need to get creative – think outside the box – consider the individual. P2) Learner is not able to demonstrate the target behavior or skill long enough to receive the reinforcer (is not successful). For example, cannot sit for the five minutes, cannot carry on a three part conversation, cannot follow the three step direction independently, etc. S2) The criteria for success is set too high. Ensure it is definitely ‘doable’ at first. Lower the standard for ‘success’/achievement to ensure the learner receives the reinforcer by demonstrating the skill but at a lesser expectation. Then, slowly build the expectation. P3) Learner was initially excited about the token economy but are no longer exhibiting the behaviours to earn the tokens or reinforcers. S3) The pricing of the reinforcer may be set too high resulting in the learner giving up before earning enough to purchase the desired reinforcer. Consider lowering the prices of the available reinforcer. This is the formal end of the reinforcer series. I sincerely recommend the use of this strategy. It has amazing potential and I have witnessed the power of it firsthand. Remember to fade the reinforcer as soon as you can and ensure that social piece remains. Set new goals, consider new reinforcers if needed and move forward! If you are interested in checking out the free online AFIRM modules, here is the link (will take you to the reinforcement module in particular as I am highlighting this here). https://afirm.fpg.unc.edu/reinforcement  This month, I will continue to highlight the EBP of ‘reinforcement’ (hence the part 2 in the title). Since there is so much to say, know and do with this powerful strategy, I decided to write multiple articles on the usage of reinforcement. Much of the information in this article is from the related AFIRM online module (link below). In this series, we have covered a variety of EBP such as visuals, self-management, prompting (parts 1 and 2) and exercise so far. While each practice can stand alone, these strategies may be used in conjunction with each other and may be referenced in these articles. In this second part, we will explore the three reinforcement procedures:

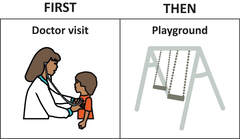

Positive Reinforcement AFIRM tells us that, “Positive reinforcement is the delivery of a reinforcer (primary, such as food, or secondary, such as verbal praise or toys) after the learner uses a target skill or behavior.” Positive reinforcement is best to use when learning a brand new skill. A simple example would be for a certain number of chores to be completed and then a set amount of time on an ipad. We ended up giving one smartie to our own kiddo for every item of clothing he put on independently when that was the target goal. This was very effective and easy! We ended up simply weaning it away with a smartie for all the ‘top clothes/bottom clothes’ then to nothing. A “first/then” agreement (verbally agreed upon or shown with a prepared visual) can be a good way to keep track of the task being completed and then the reinforcer given (as close to completion as much as possible as waiting too long may lessen the effectiveness). First, you do ___________, then you get _____________. There is a sample visual to see how simple this can be. Some people use a picture, some a picture and a corresponding word and some just the word. A general rule would be to begin with a larger reinforcer and smaller expectation and slowly begin to fade the reward while expanding the expectation. The proper pace should ensure success and allow one to keep setting new targets to reach! (Remember to have a wide variety of reinforcers so to avoid over use that may make it less motivating to earn.) Oddly enough, coffee still is my reinforcer to get out of bed after all these years! It never gets old… Token Economy AFIRM explains this as, “A type of positive reinforcement where the learner earn tokens which can be used to acquire desired reinforcers (known as backup reinforcers).” The same principles of the positive reinforcement apply but it is a chance for the person to earn ‘tokens’ toward meeting a goal to gain the reinforcer. For example, if it is a goal to ask friends different questions at lunch, then each question would earn one ‘token’ and these earned tokens can then be used to ‘cash in’ for a desired reinforcer. The learner might be able to keep track of their own tokens earned which then involves self-management as well. Win win! One could involve the learners’ interests for a themed token chart (if age appropriate and respectful depending on the person). For example, if the person is really interested in dinosaurs or trains, have that be included in the token board. See examples provided. Negative Reinforcers When I first heard of this, I immediately thought of spanking and other such ‘punishments’. That is NOT what this procedure involves. AFIRM tells us that negative reinforcers, “Remove an unpleasant or unwanted stimulus after the learner uses a target skill or behavior.” For example, when we put on a seatbelt, the dinging will stop. When we wake up, our alarm clock can stop ringing. One might be on time to work to avoid a lecture from the boss. This is to be used only after positive reinforcement has been tried and that has not been successful in meeting the target/goal. With this, the learner is motivated to meet the goal to remove something unpleasant. If you first identify preferred and non-preferred activities/items, it is easier to get started in its use. Remember to be creative with the reinforcers! Also, coupling a reinforcer with a social reinforcer (a smile, a high five, a word of praise or encouragement, chatting about their success, etc.) should occur as well. When the other reinforcer fades out, the social reinforcer can stay and may be enough motivation alone! There is still much more to the use of reinforcement, so please look to next months’ magazine for continued discussion of this important topic. If you are interested in checking out the free online AFIRM modules, here is the link (will take you to the reinforcement module in particular as I am highlighting this here). https://afirm.fpg.unc.edu/reinforcement  As you may have noticed, I have been writing a regular column highlighting one of the 27 evidence-based practices (EBPs), otherwise known as ‘things are have a lot of proof behind them that they really work’ in helping people with autism (Wong, 2016). There has been some exciting new developments in this area of study and that list has been very recently revised (2020) and now there are 28 EBPs! As an educator involved in the field of inclusive education and as a parent working to support my own kiddo, I am all about finding what really works and excited when new developments like this occur. Each month, I plan to highlight one of these (now) 28 EBPs for you. This month, I will highlight the EBP of ‘reinforcement’. Since there is so much to say, know and do with this powerful strategy, I have decided to write multiple articles on the usage of reinforcement. Much of the information in this article is from the related AFIRM online module (link below). In this series, we have covered a variety of EBP such as visuals, self-management, prompting (parts 1 and 2) and exercise so far. While each practice can stand alone, these strategies may be used in conjunction with each other and may be referenced here. One of the key ideas I like to keep in mind is that “behavior goes where reinforcement flows” (AFIRM). This is true for all people, honestly. This reaffirms our mantra of ‘good for all, critical for some’. Anytime that I am personally receiving reinforcement in my own work, home, community, I am naturally more inclined to continue the actions that got me that reinforcement. For those with autism, this is a proven, research-based practice so it is worth learning our time to investigate! There are multiple goals that can be achieved by using reinforcement strategically:

Examples of specific goals that could be addressed by using reinforcement Increase amount of time a student remains seated in class. Decrease the number of times a person interrupts a parent when on the phone or visiting a friend. Increase the practice of ‘expected’ social interactions (home, work, school, community). Increase the quality of daily/weekly grooming efforts. Decrease the ‘unexpected’ behaviors that an employer may express. *Endless possibilities depending on the specific goals for the individual. There are three basic principles of reinforcement to remember:

By delivering the reinforcement too long after the desired skill/behavior has occurred, it can lose effectiveness as the learner may not directly connect the reinforcer to their success. By having it directly after that desired skill/behavior, the learner begins to shape their behavior more often and naturally. It will also help avoid frustration for either party. If you promise the reinforcement, be prepared to give/do it right afterwards (as much as possible). Choosing the proper reinforcement is key to this strategy’s success as well. It is part of showing respect to the learner and ensuring it will be effective (short and/or long term). Having the reinforcement be something truly enforcing to the person, it has to be age appropriate as well. Making it too ‘babyish’ or beyond the learner will insult or frustrate the learner making sure the strategy will not be effective before you even start! Be sure to have more than one reinforcer though as ‘saturation’ can occur and the learner may tire of the same thing used repeatedly. The reinforcement can lose its appeal fairly quickly. Be creative with it. We often think immediately of food reinforcers but that is one of a very many to explore. A few ways to come up with a list of reinforcements: ask the person, observe them during free time to see what they may gravitate to, ask others around them, or even think about what you may often say ‘no’ to and see if that can possibly be used that (if safe, appropriate, etc.). You can look up ‘reinforcement inventories’ online for new ideas too. One lesson I have learned in my own life work, is that the reinforcer can be unexpected for us! Sometimes they are ‘not typical’ or expected but are so reinforcing for that person. For instance, one child was very motivated by smelling certain ‘smelly markers’, having his arm rubbed gently or his back tickled, calling a store to find out their hours of operation, riding an elevator, etc. There is much more to the use of reinforcement, so please look to next months’ magazine for continued discussion of this important topic. If you are interested in checking out the free online AFIRM modules, here is the link (will take you to the reinforcement module in particular as I am highlighting this here). https://afirm.fpg.unc.edu/reinforcement  This month, I plan to continue to highlight the EBP of ‘modeling’. This is part 3 of a series so feel free to look back at last two months’ articles that help to explain the strategy as there is core information is in those articles as well on modelling. In a nutshell, this is simply intentionally showing a learner what we would like them to know or do in a systematic way. I will be concluding the information on this strategy in this article. As usual, modeling can be used in conjunction with other EBPs that we have highlighted in the past, as one piece of a larger puzzle. Note: Much of the information in this article is from the related AFIRM online module (link below). There are three prerequisites before you can decide if modelling would be an appropriate strategy to use with a learner. The learner must be able to:

When the research suggests that the learner has at least some of the skills needed to complete the task, it is saying that the learner needs to have some ability to do some parts. Some parts of the skill may be teachable but having every element as a new skill will not lend itself to successful modelling. For example, if you have the goal of independently making an order at a coffee shop, the learner should know how to use a bank card or tap a credit card and be able to engage somewhat with a stranger. Some of the skills can be taught beforehand. A script of the whole exchange/order can be used to bridge nerves or issues with speaking to a stranger to help overcome this issue. The learner would watch the person modelling from start to finish and then try pieces or the whole thing on their own. This will let them know what it should look like in general which makes tasks, especially new ones, less stressful. The third point of having enough attention span to watch the modelling being done is also important. If the learner only has a few seconds of attention span (for whatever reason), the strategy of modelling would not be appropriate unless the task was only a few seconds long. Try to make the showing of the skill as short, simple and concise as possible as sustained attention is key for this strategy to be successful. This can vary greatly from learner to learner. When ADHD/ADD is a comorbid diagnosis, this aspect can be more challenging. If it is possible, but there needs to be extra or external reinforcers to ensure they are watching the model, do not be afraid to offer that to get a bit more buy in in the actual observation. For example, if sustained attention is a major issue, but the learner may watch for 1 minute versus a typical ten seconds with a promise of a reinforcement, go for it. If a piece of gum will get them observe the model longer, great! Lastly, use modeling as a ‘primer’ or as a ‘prompt’. That simply means to use it at the very beginning of a new skill (primer) to show the learner what the final outcome is to look/sound like or use modelling in the middle of teaching the still if they have forgotten all or part of the skill. For example, you want the learner to learn to remember to lock up at night, show them all the parts of that (lock doors, ensure stove is off, turn off lights, turn down heat, etc.) at the beginning of the learning process. They simply observe. (Make a checklist if needed – visuals prompt). When you use modelling as a prompt, the learner usually can do it independently or can do most of it independently after being taught/practiced, but for some reason forgets how or a portion. You can use modelling as a way to support the process again. If they learner remembers to do all the night lock up items but forgets the door locking, one can model that part for them again if needed. This wraps up my mini-series on modelling. I hope that you have found it helpful and has helped to add one more evidence based practice into your toolkit of positively supporting someone with autism. Honestly though, this strategy really fits into that mantra of ‘good for all, critical for some’. The popularity of ‘how to’ you tube videos lends itself to the effectiveness as well. Video modelling is actually counted as a separate EBP but is definitely related. It is very helpful to learners with any sort of language delay as there is more to watch than to listen to or understand/process at one time. If you are interested in checking out the free online AFIRM modules, here is the link (will take you to the social narrative module in particular as I am highlighting this here). https://afirm.fpg.unc.edu/node/589 |

Filter Posts by Topic

All

AuthorCarmen has been published in a variety of online and print articles. Writing is a passion and she strives to grow and share her message. |

Photos from shixart1985 (CC BY 2.0), JLaw45, Goat Tree Designs, osseous, wuestenigel, shixart1985

RSS Feed

RSS Feed